Editor's Note: We’re a company made up of people who occasionally have opinions about important things happening in the world. We also think that corporate citizens have a responsibility to engage in social discussions, even when they have no direct bearing on herbalism and Chinese medicine. Posting these essays to this blog should be considered an experiment, and we welcome your comments, even if they are to tell us to cease and desist.

JUST AS I WAS GEARING UP to rage against another daft decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, it surprised me yesterday by ruling unanimously in a case with far reaching implications for medical ethics and post-personal property law. It said, in essence, that sections of naturally occurring human DNA may not be patented. That might seem self-evident, but it reverses three decades of official practice to the contrary.

This means that a number of biotech firms that have been busy patenting human genes — giving them the right to sell, license, or otherwise make money on them — will need to rethink, radically and rapidly, their business models. No doubt these companies and their shareholders will see the court’s decision as a setback, and I can understand why. After all, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has long given them good reason to expect a different outcome; for 30 years, it has awarded patents on human genes to companies like Myriad Genetics, prompting investors to pour billions of dollars into their coffers. In turn, these corporations have used their patented genes to develop exclusive and lucrative biotech products, such as Myriad’s test for BRCA, a gene whose mutation can indicate a predisposition to breast cancer. If BRCA rings a bell, it’s because Angelina Jolie’s pre-emptive mastectomy announcement put the BRCA gene test in the news lately.

The upshot of the court’s ruling should be (though I’m cautious about predictions when such sums of money are involved) greater access by researchers to previously proprietary genetic discoveries, which would in turn lead to more innovation, increased competition, lower prices, and greater patient access to genetic testing products. Let’s hope so. But what energizes me most about the court’s opinion is that it shines much needed light on a question that requires serious debate: who owns our most personal of personal property, namely our biological bodies and all the underlying chemistry and processes within them?

Until now, the answer has been: It belongs to whoever isolates it and patents it first. And it all started with a modest but controversial mouse.

Of Mice and Money: Profiting from the First Patented Mammal

The issues surrounding botanical and biological ethics are old and ongoing. Currently, the topic of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is in the news again. The latest dustup is the discovery of unapproved GMO wheat growing in Oregon, which prompted Japan to cancel the importation of 25,000 tons of U.S. wheat. In turn, farmers in Idaho are suing Monsanto for negligence leading to lost sales.

But while most of us think of crops when we hear mention of GMOs, not all GMOs are limited to the plant kingdom. I remember reading some 25 years ago about Harvard University scientists who had “invented” a mouse with a predisposition to develop cancer, something useful to oncology researchers. While some decried the engineering of an entire animal breed destined to suffer horribly for medicine, it wasn’t until the scientists took steps to commercialize their work that the hoopla began in earnest: those steps were to brand, trademark, and patent their creation as OncoMouse® — the first mammal ever to be patented. To turn their creation into cash, they then licensed it to DuPont.

And that’s about when the language used to talk about a certain class of living, breathing organisms began to change to something corporate and, frankly, hideous. Fortune magazine named OncoMouse “Product of the Year.” In legal agreements, DuPont and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) described the lab mouse as “DuPont’s proprietary OncoMouse® transgenic animal technology,” and they agreed to terms for use by the NIH as long as that use could happen “without compromising DuPont’s ability to receive appropriate value from commercial applications of the technology.”

Personally, I find something unnerving and inhuman about this choice of words. Describing a mouse as a “product” and “technology” succeeds at stripping the life from it and, since we have little feelings of distress or guilt over our treatment of inanimate objects, it permits us to exploit a life form for profit without the burden of moral concern. But then, we humans have a long history of doing just that when it suits us, even to members of our own species.

Wherever you stand on the broader issue of animal rights, the OncoMouse story should make you shiver, not only because it demonstrates how far humans have strayed from our own place in nature, but because it opens the door to a growing menagerie of genetically altered species whose existence stretches attempts at justification, like featherless chickens, glow-in-the dark rabbits and Ruppies, and Enviropigs.

Fluorescent Fish and the $28,000 Cat

Many of the transgenic animals “created” to date are arguably useful to medical research, but though the modifications seem to cause little or no harm to the animals themselves (with the exception of the tumor-fated OncoMouse) and have the potential to do great good, there’s no avoiding that these animals are bred for scientific testing and have little expectation of life outside the lab. Meanwhile, other examples of transgenic animals seem to be designed solely for commercial purposes.

Take GloFish® for example, the first animal produced using recombinant-DNA technology “approved for use” by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (though it’s not clear to me if they’re approved as a food or a drug). These genetically-modified zebrafish have been illuminated through the insertion of a green fluorescent protein. Additional gene “constructs” allow for the production of yellow and red hues, though personally I’m partial to Galactic Purple. All things considered, GloFish appear to be a benign application of transgenic technology. Still, what fate awaits the progeny of day-glo minnows when their novelty wears off is yet to be seen, at least with the lights on.

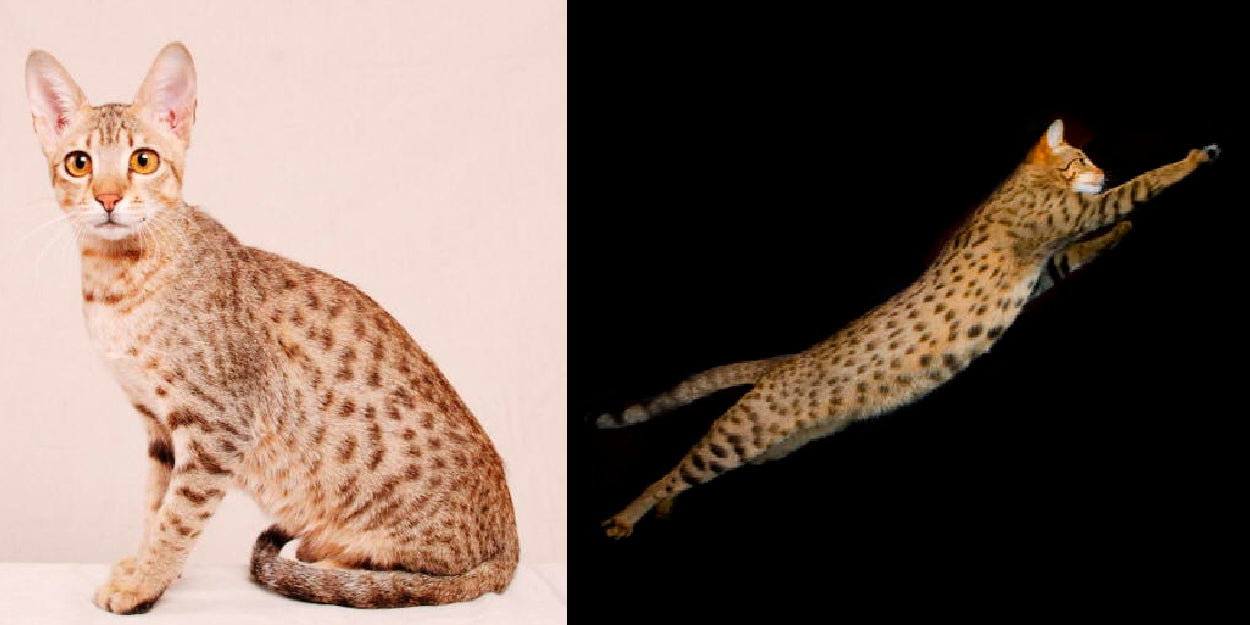

Hypoallergenic cats are among the new breed of designer animals made possible by advances in genetics.

Hypoallergenic cats are among the new breed of designer animals made possible by advances in genetics.

If genetically designed pet fish seem acceptable, then the idea of a line of genetically modified hypoallergenic cats and dogs seems equally benign — at least on the surface. LifeStyle Pets is one such purveyor of sneeze-free felines, with starter cats priced at $6,950 and the top-of-the-line Ashera GD model going for a cool $27,950. Or you can get a sniffle-less pooch for a mere $15,950. Be sure to budget an extra $795 for delivery in the U.S.

For animal lovers with pet allergies, this “production” of hypoallergenic dogs and cats must seem like a godsend, even if the most exotic cat does cost 38 times the average per capita income of Haiti. And the poultry farmer who can reduce his air conditioning and plucking costs by raising featherless chickens can crow about making food cheaper and thus more available to the poor. But history argues against the notion that feeding the less fortunate is his main motivation.

The inventor of the featherless chicken says having no feathers keeps the chickens cooler. That the breed has more health problems is apparently offset by the money and trouble saved in plucking the birds during processing. I can't help wondering who has the job of applying the sunscreen, and whether that allows them to be marketed as pre-basted.

It also argues against the idea that corporations involved in high-science will self-regulate, stopping short of serious ethical violations because their conscience demands it. Most people — whether you accept that corporations are people or not, people run university labs and corporations — simply don’t have that kind of will power, especially when major fortunes are at stake.

And that’s why the Supreme Court’s decision is an important and encouraging step. It may rein in the profit potential of companies rushing to cash in on snippets of human genetic code, and thus slow the transgenic technology train. But it doesn’t go far enough. As long as the decision fails to include all animal DNA, the business model is only bruised, not broken. What’s to stop research scientists from patenting the genes of chimpanzees and bonobos, which share 99% of of their DNA with humans? Or mice, which have 97.5% of DNA in common with us? Or a banana tree, with 55% of its DNA that same as ours? How is it possible to own something that is possessed by nearly every living thing?

The truth is, when it comes to DNA, all genes are fundamentally community property. We should view them as the biological equivalent of National Parks, a resource available to everyone and protected legally from the biological piracy of appropriation, exploitation, and profiteering by the few.

1 comment

Just like breeding Mexican Hairless Dogs?